How well has Britain treated the Jews?

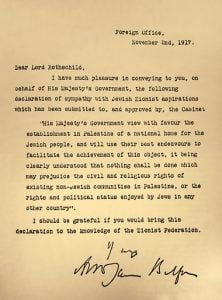

This week marks the 100th anniversary of the Balfour Declaration which paved the fashion for the establishment of the modern Country of Israel 30 years later on. The seemingly intractable controversy created past Balfour was summed up by the Hungarian-built-in Jewish writer Arthur Koestler, who quipped, "one nation solemnly promised to a second nation the country of a tertiary". The Declaration is frequently idea to be the product of a relatively modernistic move for the concrete restoration of Jews to a geographical homeland—but in fact British welcome and back up for Jewish people goes a long fashion back into a very mixed history.

This week marks the 100th anniversary of the Balfour Declaration which paved the fashion for the establishment of the modern Country of Israel 30 years later on. The seemingly intractable controversy created past Balfour was summed up by the Hungarian-built-in Jewish writer Arthur Koestler, who quipped, "one nation solemnly promised to a second nation the country of a tertiary". The Declaration is frequently idea to be the product of a relatively modernistic move for the concrete restoration of Jews to a geographical homeland—but in fact British welcome and back up for Jewish people goes a long fashion back into a very mixed history.

The latest Grove Ethics volume, British Christian History and the Jewish People past James Patrick, charts this controversial (and controverted) history in unusual particular, and in doing so unearths some remarkable aspects of Britain'southward relationship with Jewish people. British affection for the Jews is cached deep within some fundamental moments of our history.

Christianity is pervasive in the British Isles, long thought to accept been introduced by first-generation followers of Jesus—fellow Jews—every bit early as the first century AD, manifestly attested by Eusebius (Dem Ev III.5.112). In whatever example, by Advert 200 Tertullian could refer to 'the haunts of the Britons, inaccessible to the Romans but subjugated to Christ' (Adv Jud 7.4)…

In the late 800s, King Alfred the Great start unified Anglo-Saxon tribes into the nation of England, and this new national self-identity was inspired by State of israel'due south tribes whom Moses united into i nation. Alfred was a lover of learning, credited in later on centuries with founding the first schools in Oxford which subsequently developed into the academy. He taught himself Latin in order to translate of import Christian texts into Former English, and even began his royal English constabulary code, called Alfred'south Dooms (the foundation for British common police), with translations of Moses' laws from Exodus (20.1–17; 21.1–23.9, 13). Alfred justifies this reapplication to Christian England by citing Jesus' affrmation of the ongoing value of Israel's police force (ie Matt 5.17–xix). He and so traces the connection to the Gentiles by translating in full the legal ruling of the Council at Jerusalem (Acts 15.23–29), issued by apostles of Jesus to 'heathen nations.' His 'English race' is thus positioned as i among many who had received the 'constabulary of Christ' (the Golden Rule is added from Luke 6.31 in its negative form). There is no hint of supersessionism here, but rather an illustration of the ancient prophecy that 'the constabulary will go forth from Zion…and he will make decisions for strong nations far away' (Micah iv.two–3).

Having outlined a general sense of solidarity of British Christians with Jewish perspectives, James Patrick then explores the reception of actual Jewish communities following the Norman Conquest of 1066.

Christians had adopted for themselves the Old Testament prohibition confronting lending money with interest. Jews, on the other hand, were denied participation in trade guilds on religious grounds, and were therefore finer barred from nigh professions. Their limited options led them into banking and consequently some of them became quite wealthy. The Norman kings gave straight regal protection to the Jewish customs, which non just made them and their possessions the property of the male monarch, but likewise isolated them from the feudal fabric of life in which everyone else found their proper place. Jewish moneylending became a personal source of finance for the king, enabling castle building and military spending, and freeing him from over-reliance on his powerful barons and retainers. The Jewish community, living amongst their Christian neighbours in roughly two dozen towns throughout the country, provided of import nancial services to the local economy. Yet their unique status and privileges were oft resented past their neighbours, and sometimes put them in danger of violence from barons in their debt.

Notwithstanding, the first hundred years of their presence in England was generally peaceful. Jewish financiers kept business deeds in cathedral treasuries, enjoyed splendid and free relations with some of the great religious houses such equally Canterbury, and entrusted their women and children to monasteries for safekeeping in times of disturbance. Aaron of Lincoln was the wealthiest person in England when he died in 1185, his vast estate requiring the cosmos of a special Exchequer of the Jews, and his loans had apparently even helped to build the cathedrals of Lincoln and Peterborough. Open debates between Jewish and Christian clergy about religious di erences were not uncommon, and conversions are attested in both directions, sometimes for reasons of intermarriage. As well every bit issuing a lease that protected the basic rights of Jews, Henry I also made sure that monks were sent to all the main towns with a Jewish population to defend the orthodox religion against Judaism. Towards the end of that century in continental Europe, the Tosafist rabbi Elhanan ben Yitzhak recorded concern 'that in the country of the Isle [England] they are lenient in the matter of drinking stiff drinks of the Gentiles and forth with them.' Christians were evidently going down to the local pub with their Jewish neighbours!

Only the role of the Jewish customs equally financiers and therefore power brokers in the key political conflicts was not to end happily, and it led to the expulsion of the Jews from England in 1290 amidst much mortality. Three hundred years afterwards, the Jewish people became important over again in British Christian thinking with the translation of the Bible into English during the Reformation period.

In 1545, ane of the starting time English Protestant Bible scholars, called John Bale, published a commentary on the Book of Revelation from exile in holland, haven also for Jews exiled from Spain and Portugal. He interpreted the 144,000 of Rev 14.one–v literally as 'the Iewes or Israelytes that shall in this latter age be converted unto Christ,' likewise citing Old Testament prophecies. Among these, he cited (and thereby began to fulfil) Jer 31.10—'Hear the word of the Lord, O nations, and declare in the coastlands afar off, and say, "He who scattered Israel will gather him and go along him as a shepherd keeps his flock."' Bale's views were further popularized by his friend John Foxe, writer of the hugely influential Actes and Monuments (ie Book of Martyrs, 1563). During Edward VI'southward short reign, the continental Reformed scholars Martin Bucer in Cambridge and Peter Martyr in Oxford both taught that there would exist a future national conversion of the Jews.

Recognizing that the Jews were promised a national spiritual restoration, through faith in the Messiah, was the first step toward too acknowledging their promises of a national physical restoration. Certain enough, in the offset decade of the 1600s, the Cambridge scholar Thomas Brightman wrote his commentary on Revelation, and holds the stardom of existence the first Puritan (thoroughgoing Protestant) writer to argue clearly that the Scriptures predict a concrete render of the Jewish people to Jerusalem. He proposed that the 'kings from the eastward,' who cross through the stale-up River Euphrates at the 6th bowl in Rev xvi.12, are to exist identified as the Jews. 'But,' he says, 'what need there a style to be prepared for them? Shal they returne agayn to Ierusalem? There is nothing more certain: the Prophets plainly confirme it, and beat out oft upon it.' He believed that this return, which would include the ten lost tribes, would finally defeat the Muslim Ottoman empire that had conquered Jerusalem in 1517 and now threatened Europe.

Information technology is fascinating to come across how these views, at showtime quite marginal, began to spread, and Patrick notes the manner that this perspective gained wider support across this Puritan outlook.

Within Britain, expectation of Jewish spiritual and physical restoration had spread beyond Puritan evangelicalism into wider British consciousness. The philosopher John Locke assumed this in his 1707 Paraphrase and Notes on the Epistle of St Paul to the Romans (paraphrase of 11.23). In 1721, the hymnist Isaac Watts urged his London congregation that upon seeing '1 and some other of the Jewish nation in this smashing urban center,' zealous for their own religious traditions, and so 'we should permit our eyes affect our hearts, and drop a tear of compassion upon their souls,' and pray for the soon fulfilment of biblical promises for their spiritual and concrete restoration (Sermon Xix, on Rom ane.16). In 1733, Sir Isaac Newton published posthumously a work on the prophecies of Daniel and Revelation, which assumes that the Jews must return and rebuild Jerusalem. Reflecting on prophetic details in Dan 9.25, he wondered very practically whether the prophesied '"commandment to return" may perhaps come forth non from the Jews themselves, but from another Kingdom friendly to them.'

This view continue to get together momentum during the eighteenth century, and led to serious political expression in the nineteenth.

The British evangelical car that began to power the political motion for Jewish restoration, culminating 100 years later in the Balfour Declaration, was in fact designed by Jewish Christians and built out of German language parts. Since mission was already well established in German Pietist and Moravian churches, at outset they also supplied most of the missionaries for the new British missions. One of these, a German-Jewish catechumen called Joseph Frey, set in 1809 a new London Social club for the Promotion of Christianity amongst the Jews, normally chosen the London Jews' Guild [LJS]. Rapidly drawing the attending of wealthy evangelicals, both Anglican and nonconformist, its showtime patron was the Duke of Kent (before his girl Queen Victoria'due south birth). Its headquarters were built on the edge of the largely Jewish Eastward End of London in a campus called Palestine Place, modelled after Pietist missionary institutions in Halle, and staffed past gifted Hebrew-speaking scholars such as Alexander McCaul of King'south Higher London. Initially reaching out to the Jewish community in London, their attention shortly turned to those on the continent and as well throughout the Middle East, inspired by the remarkable travels of the Jewish-Christian 'apostle' Joseph Wolff.

The ii most influential evangelical Anglican ministers in the first half of the nineteenth century were both tireless promoters of the LJS all around the country—Charles Simeon in Cambridge, and Edward Bickersteth. The same was true of their shut friends (respectively), William Wilberforce and Lord Shaftesbury, each in their turn also known as the moral vocalism of U.k. for their fearless advocacy in Parliament on behalf of the poor and needy across Great britain's vast empire. In 1818, the financial benefactor of the LJS, Lewis Way, was invited by Czar Alexander I to present a well-received paper on Jewish emancipation to the crowned heads of Europe at the international diplomatic briefing in Aix-la-Chapelle, post-obit Napoleon's defeat.

In the final chapter of his booklet, James Patrick traces the complex history of the outworking of the Balfour Declaration, and the electric current status of Israel in the lite of that. Inevitably, this involves interpreting the facts in a item way—and not all will concord with his interpretation. But the booklet demonstrates that the Balfour Annunciation and British relations with the State of Israel are not mere modernistic phenomena only have deeps roots in British history. It is a fascinating read, and provides essential background for interpreting the events of 100 years ago.

In the final chapter of his booklet, James Patrick traces the complex history of the outworking of the Balfour Declaration, and the electric current status of Israel in the lite of that. Inevitably, this involves interpreting the facts in a item way—and not all will concord with his interpretation. But the booklet demonstrates that the Balfour Annunciation and British relations with the State of Israel are not mere modernistic phenomena only have deeps roots in British history. It is a fascinating read, and provides essential background for interpreting the events of 100 years ago.

British Christian History and the Jewish Peopletin exist ordered from the Grove website for £3.95 (mail-gratis in the Britain) or as a PDF ebook.

Follow me on Twitter @psephizo.Like my page on Facebook.

Much of my work is washed on a freelance footing. If you take valued this post, would yous considerdonating £1.20 a calendar month to support the product of this blog?

If you lot enjoyed this, exercise share it on social media (Facebook or Twitter) using the buttons on the left. Follow me on Twitter @psephizo. Like my page on Facebook.

Much of my piece of work is done on a freelance basis. If y'all have valued this post, you lot can brand a single or repeat donation through PayPal:

For other ways to support this ministry building, visit my Back up page.

Comments policy: Good comments that engage with the content of the postal service, and share in respectful debate, can add real value. Seek first to sympathize, then to be understood. Make the about charitable construal of the views of others and seek to learn from their perspectives. Don't view debate as a conflict to win; address the argument rather than tackling the person.

Source: https://www.psephizo.com/reviews/how-well-has-britain-treated-the-jews/

0 Response to "How well has Britain treated the Jews?"

ارسال یک نظر